Apple’s approach to NFT apps is still something of a gray area. The company permitted NFT marketplace OpenSea to launch an app, but only for browsing NFTs — not for buying and selling them. The same goes for Rarible’s iOS app, which is described as an NFT browser for “viewing” blockchain collectibles. Other NFT apps offer similar discovery features. But the lack of official guidelines around NFTs on iOS has made it hard for app developers to know where the line is in terms of what’s permitted and what’s not.

One developer who experienced bumping up against the line first-hand is Alan Lammiman, founder of Daily Apps.

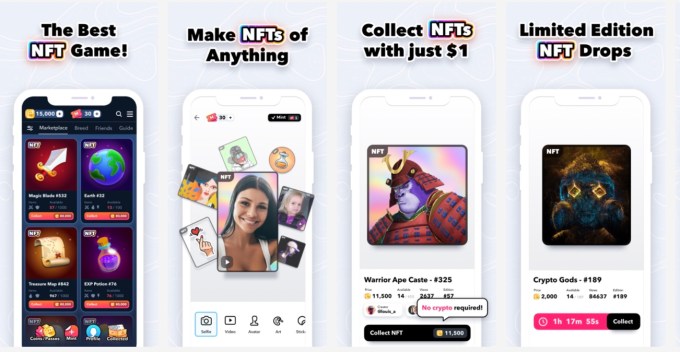

Lammiman created the mobile-native “NFT” marketplace app Sticky, which had been live on the App Store for several months before Apple removed it. During this time, Apple approved over half a dozen updates to the app that used the term “NFT” in the same manner that ultimately led to the app’s removal. But Apple eventually told Sticky that it was misleading to use the term “NFT” for digital collectibles than weren’t minted to a public blockchain. It did not give Sticky time to make changes to the app before pulling it down, Lammiman said.

Sticky’s app had been operating in a hazy area, to be fair. It was using a proprietary, private ledger, which it disclosed in the app’s App Store description. The company also explained to users that its NFTs were “collectibles,” but not “securities, convertible currencies, or investments.”

The removal serves as an interesting example of how Apple is deciding what’s permitted on the App Store and what’s not. It’s also another indication of how Apple seems to be making decisions on the fly as it tries to address developers’ use of new technologies and terminologies.

Image Credits: Sticky

For a while, at least, it seemed Sticky had found a loophole in Apple’s unspoken rules for NFT apps.

As its name implies, Sticky began as a tool for creating stickers back in 2020. But it later redesigned to focus on NFTs when it couldn’t make the earlier model work financially. The revamped app began to gain traction around December 2021 and received positive feedback. Sticky began to fundraise, Lammiman said.

The most recent version of the app allowed creators to mint “NFTs” on Sticky’s ledger. Users could also only sell items made in Sticky within Sticky, where the NFT images appear watermarked unless you own them. This prevented them from being copied and resold on other marketplaces like OpenSea, the company said. Sticky’s transactions were made using “StickyCoin,” which is not a cryptocurrency. The StickyCoins themselves were bought in packs using standard in-app purchases.

Lammiman explained this decision was an attempt to play by Apple’s rules.

“Apple has several restrictions on cryptocurrency apps,” he said. “Although none of the rules appear to explicitly forbid offering an in-app currency that is also a cryptocurrency, we thought it would be best to avoid that issue, so StickyCoins are just a regular in-app currency.”

Creators could only “cash out” on their “NFT” sales after meeting anti-fraud requirements, including providing their real name, photo, and address. Sticky claimed it checked artwork for plagiarism prior to payment and would request additional evidence of authenticity for any art in question. (We cannot verify this as the app is now gone). Payments were supposed to be sent to creators through PayPal at the end of the month — the StickyCoins themselves weren’t convertible to cash.

At the time of removal, Sticky only allowed primary trading; it said secondary trading features were under development. This had disappointed users who felt secondary sales should be a part of any NFT marketplace.

Not an “NFT” app

But — and this is a big but — Sticky’s ledger was not a decentralized or open-source blockchain, like the networks that support Bitcoin and Ether. It’s a proprietary centralized ledger system operated by Sticky with zero transparency.

This wades into a tricky area. Apple suggested that Sticky’s use of the word “NFT” to describe its digital collectibles was misleading because they weren’t minted on a decentralized, public blockchain. The NFTs didn’t have typical blockchain addresses and weren’t bought and sold using cryptocurrencies. In fact, it’s hard to prove a ledger even existed here.

Many users also agreed these were not what they considered to be NFT transactions.

A number of user reviews (cached by Sensor Tower before the app’s removal) were from people who called Sticky a scam or misleading because the collectibles were bought using in-app coins, not cryptocurrencies as usual — complaints Apple’s feedback also mirrored. The lack of secondary trading was often mentioned, too.

Image Credits: Sticky App Store review

Sticky tried to appeal its App Store removal. It submitted an update that would allow users to export their NFTs collected in Sticky to a public blockchain.

This was intended to assuage fears over Sticky’s control of its ledger and complaints that its use of the word “NFT” was misleading to users. The updates were submitted on March 12, 2022 — two days after Apple told Sticky for the first time it could not use the word “NFT” in the manner it had been. The app has been under reveiew ever since and the updates have not been approved.

The company notes it has not been able to submit updates or bug fixes to existing users. Sticky has tried to follow up with Apple several times via email and phone, but only got voicemail. Apple’s email response advised the company to wait for a decision:

“I understand that you are concerned with waiting longer than you have anticipated for your app to be reviewed. The review for your app is still in progress and requires additional time. We will provide further status updates as soon as we are able, or we will contact you if we require additional information.”

And while what Sticky was doing wasn’t necessarily wrong or explicitly banned by the App Store Review Guidelines, it was operating in a questionable space by offering a proprietary ledger that didn’t have a developer platform, whitepaper or any way for the public to contribute. Its website only said it “was looking into” making the ledger open-source and to “stay tuned.” This made it different from other entities that were using proprietary ledger systems. For example, NBA Top Shot was built on its own blockchain, but it was also more transparent about how it worked and allowed the public to contribute.

For consumers, that meant there was a risk to using Sticky’s service. Sticky controlled the entire system, so it could have shut down or rewritten its network at any time, and users could have lost their work and collections. It appears Apple made a gut call here in favor of consumer protection. Arguably, it may have been the right one. (Apple didn’t respond to a request for comment.)

While the risks to consumers are apparent and Apple’s decision certainly makes sense, what’s concerning is that this app was approved to operate in the first place. Sticky also wasn’t given a chance to correct its problems before removal, which seems unfair; in the worst-case scenario, Sticky could have returned to being a sticker app while it sorted things out.

But the larger issue is that developers like Sticky don’t have access to clear and documented rules that explain how NFT apps should or should not operate on the App Store. They’re left to feel things out by submitting ideas, seeing if they get in, then waiting to see how long the ride lasts.

Sticky had 484,000 lifetime installs before its removal from the App Store, Sensor Tower data indicates. The app had accrued 1,125 reviews and 26,273 ratings and had an approximately 4.6-star rating.

Lammiman said the business would not survive this ban which is why the company chose to make its issues public.

Update, 4/7/22, 4:13 PM: 45 minutes after publication of this article, Sticky was allowed to return to the App Store.

from TechCrunch https://ift.tt/Uvdcbuk

via Tech Geeky Hub

No comments:

Post a Comment